Find out about the current research interests in the van Ooijen lab.

Our research

We all experience cycles of day and night resulting from planet Earth’s rotation around its axis. Humans, other animals, plants, fungi, and some bacteria have evolved a biological clock, or circadian clock, to anticipate this rhythmicity.

Circadian rhythms are the appropriately 24h rhythms in the behaviour, physiology, or metabolism of an organism or cell, and are a fundamental feature of life on Earth. Circadian disruption, for example observed in shift workers (one in five of the UK workforce!), increases the risk of infectious diseases as well as the risk of metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, depression, and even some types of cancer. The clear importance of our body clock for health warrants a full understanding of the mechanisms behind circadian timekeeping.

Whole-organism circadian rhythmicity is ultimately a culmination of circadian rhythms in every single cell. Every cell in your body individually keeps time! And in the living cell, virtually nothing stays the same over the course of a day. In our lab, we study the mechanisms and functional consequences of biological timekeeping at the molecular and cellular level.

Research into circadian timekeeping and rhythmic regulation of metabolism is hampered by multiple layers of complexity: population effects, separate but coupled clocks in different tissues, coupled cellular oscillators within tissues or regions of tissues, and an incredible complexity of genetic networks in the clock of every individual cell. Additionally, genomic redundancy and higher ploidy levels in traditional model organisms are a key hindrance in the genetic dissection of clocks.

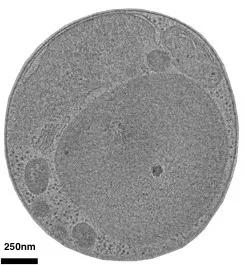

A major research line in our lab is to use experimentally tractable model cells of minimal complexity to rapidly generate fundamental understanding of timekeeping. Using the prototypical eukaryotic cells of Ostreococcus tauri, some of our overall aims are to answer the key questions: How do cells keep time? How does a cell align metabolism to the environmental rhythm? Through comparative biology, where results from our model cells are translated to complex organisms that are experimentally less tractable, our fundamental cellular research is expected to directly impact areas of major human challenges, such as human and veterinary health or crop improvement.

Comparative chronobiology

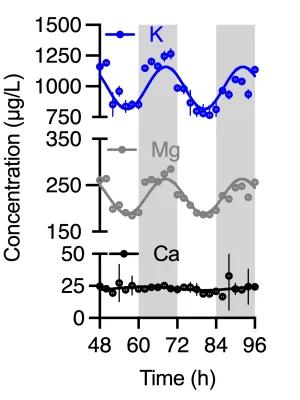

We primarily use the model cell Ostreococcus tauri to subsequently test our results in mammalian cells. Ostreococcus has only ~8000 genes, similar to yeast, but unlike yeast they have a strong circadian clock that is coupled to the cell cycle as it is in human cells. Evidence from our lab indicates that the blueprint of cellular circadian organisation translates well from this model cell type to human cells: in 2011 we showed that pharmacological treatments affect the clock in human cells and Ostreococcus identically. We revealed a circadian rhythm in cellular redox state that was identical in Ostreococcus, human cells, and other rhythmic life. In 2016, we revealed circadian oscillations in ion concentrations in Ostreococcus, human, mouse, and fungi. In 2020, we reported that the methyl cycle affects circadian rhythms identically in human cells, Ostreococcus, and more. As one of the world leaders in using this cell type, our lab is extremely well placed to exploit its potential and generate shifts in understanding of cellular circadian rhythms.

Functional contributions of ion fluxes to cellular circadian organisation

Our work established that circadian rhythms in the intracellular concentrations of potassium and magnesium are pervasive in human cell types, as well as in other eukaryotes. These ion rhythms functionally affect some of the most fundamental aspects of cell biology, including translation, cytoplasmic conductivity, and proteostasis. A large part of our research activity pursues hypotheses into key regulatory functions that ion rhythms might have in the circadian organisation of the cellular landscape. For example, we believe that intracellular potassium levels orchestrate circadian rhythmicity and cell division.

This project, and several of our other new and exciting directions, involve close collaboration with our friends in the Priya Crosby lab, next door:

Find our more about the Crosby lab

This article was published on