Outline of the research areas in the Julia Richardson Group.

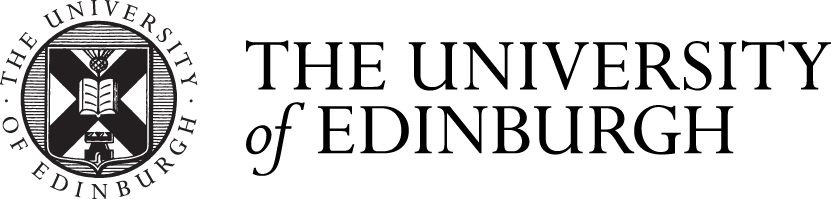

DNA ligase enzymes play a key role in DNA replication, repair and recombination by joining strands of DNA whenever new DNA is being made or when damaged DNA is being repaired. They catalyse phosphodiester bond formation by a three-step reaction mechanism that characteristically uses either NAD+ or ATP as the energy source. Recently we have identified a group of bacteriophages, the T5-like phages, that encode a novel split DNA ligase, which is (unusually) composed of two sub-units. These form a dimer with NAD+-dependent DNA ligase activity. We propose that there is a connection between the split DNA ligase and a second highly distinctive feature of the T5-like phage: the presence of single-stranded nicks in the linear dsDNA packaged genomes.

We are using structural and biochemical methods to investigate the impact of the split on the overall architecture of the split DNA ligase, it’s interactions with the nicked substrate DNA and its reaction mechanism. This project is in collaboration with Dr Stuart MacNeill (University of St Andrews) and is funded by the Leverhulme Trust.

Dr Stuart MacNeill - University of St Andrews website profile (st-andrews.ac.uk)

DNA transposition

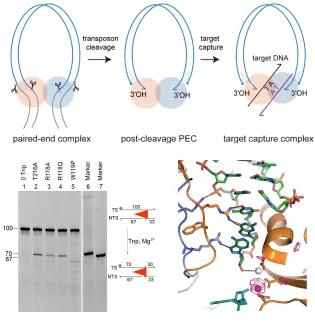

Transposons make up a large proportion of most genomes and can move from one place to another, driving evolution and creating genome instability. Jumping genes have also given rise to new, useful cell functions e.g. V(D)J recombination and the adaptation process of CRISPR-Cas adaptive immunity. Eukaryotic DNA transposons (including Sleeping Beauty) are also useful tools for genomic manipulations.

At the mechanistic level, DNA transposition is related to HIV-1 integration and V(D)J recombination. To establish in molecular detail how DNA transposons move, we have determined structures of nucleoprotein complexes that form along the transposition pathway of the mariner transposon Mos1. They reveal how the transposon is cut from host DNA, and how the ends are held together and then inserted at a new genomic location. These findings have implications for our understanding of DNA rearrangements more broadly and will advance biotechnology applications of transposons.

DNA repair

Topoisomerases relax supercoiled DNA, allowing transcription/replication machinery access to the DNA in order to copy or replicate it. They do this by forming a transient 3' phosphotyrosine complex, which breaks a DNA strand and allows unwinding. Usually the broken DNA strand is repaired, but, if the Topo-DNA complex is stalled, potentially toxic double strand breaks can form. Anti-cancer therapies, such as camptothecin, exploit this by preventing repair of such Topoisomerase-induced DNA damage.

The DNA repair enzyme tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 1 (Tdp1) is the cell's back up plan: it can process stalled Topo-DNA complexes by hydrolysing the phosphotyrosine bond between Topo IB and a 3’ DNA phosphate. In collaboration with Dr Heidrun Interthal, we are using structural and genetic approaches to understand in molecular detail how human Tdp1 recognises and processes its physiological Topo IB-DNA substrates.

This article was published on